Dance History Final Project – Lecture-Demonstration

Ballet Portion:

• Use the reading and lecture notes for reference. It is not necessary to do further research.

Fokine & Diaghilev:

Yarimar Navarro

Writing prompt:

• What kind of change did Fokine make during the Diaghilev period?

Keiara Avinger:

Writing prompt:

• Who is Diaghilev? Choreographer? Dancer? Impresario? What did he actually do?

Anna Pavlova

Taila Greer: (You need to coordinate with Isadora Duncan)

Writing/speaking prompt:

• What is Anna Pavlova most famous for?

• What is her connection to Fokine & Diaghliev?

• How was her dancing influence by Isadora?

Performance piece:” The Dying Swan”. Music provided: Saint-Saens

Romantic Period:

Speaking assignment:

As group talk 5 min about Romantic Period: What is Romantic Period? Between what years was the Romantic period? How the ballet Technique& Costumes developed during the Romantic period? Talk about the influence of Marie Camargo & Salle in Romantic Period. Show a video clip not longer than 3 min what illustrates Body line, costumes and Pas de deux.

Bianca Distefano

Writing prompt:

• From the Arts prospective (music, literature,….etc)what are characteristics of Romanticism?

Brett Bell

• Who is Bournonville? Name some of his works.

Shakima Bowie

• Make a list of characteristics of Romantic Ballet.

Ruth Etheart

• Who are the four characters in Pas de Quatre& how did the ballet “Pas de Quatre” developed.

Aura Tavares

• Write about Ballet & Opera in 1800. Connect Romantic to the Renaissance

Karen Cedant

• Write with your own words the plot of “La Sylphide”

Gabriela Silva

• Write about the importance of Male & Female dancers in Romantic period. What is Pas de Deux? Compare and connect the Romantic ballet with Classical ballet.

Classical Period:

Speaking assignment:

As group talk 5 min about Classical Period: What is Classical Period? Between what years was the Classical period? How the ballet Technique& Costumes developed during the Classical period? Talk about the influence of Marius Petipa & Lev Ivanov. Show a video clip not longer than 3 min what illustrates Body line, costumes and Grand Pas de Deux.

Phania Exavier

• Write and explain about the second Petipa “Ingredient” Spectacle.

Rachel Klein

• Write and explain about the 5th Petipa “Ingredient” Grand Pas de Deux. Compare and connect between Classical ballet and Romantic ballet.

Taylor Oliveira

• Write and explain about the first Petipa “Ingredient” Grand classical style. Write about the importance of Male & Female dancers in Classical period.

Stephone Nicholas

• Write and explain about the 6th Petipa “Ingredient” Finale. Compare and connect Classical ballet with Diaghilev period.

Takia Richardson

• Write and explain about the 4th Petipa “Ingredient” Choreographic variety. Compare and connect Ballet Comique de la Reine with Swan Lake (costumes. lines, length of performance dancers)

Ivana Rodrigues

• Write and explain about the 7th Petipa “Ingredient” Classical style. Compare and connect Swan Lake with Giselle (costumes, body alignment, technique, performance length, scenery).

Fedner Dorrelus

• Write and explain about the 3rd Petipa “Ingredient” Virtuosity. Compare and connect the technique (Virtuosity) from classical ballet and renaissance.

Modern Portion:

• Use the reading and lecture notes for reference. It is not necessary to do further research.

• Speak in first person

Isadora Duncan: (You need to coordinate with Anna Pavlova)

Yarimar Navarro

Writing/speaking prompt:

• What were your inspirations?

• What are you dancing about?

Keiara Avinger:

Writing/speaking prompt:

• What were you trying to break away from with your art?

• What was your influence to the ballet world (specifically Diaghilev, Fokine and Pavlova) and the development of modern dance as an art form?

Performance piece: 1 min dance in the style of Isadora Duncan, wearing a tunic. Music provided: Brahms waltz.

Denishawn: Ruth St. Denis & Ted Shawn

Shakima Bowie: Ruth St. Denis

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Your first inspiration for dance

• What were some characteristics of your dances and what did they meant to you?

Ruth Etheart: Ted Shawn

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Your connection to Ruth St. Denis

• Some of your major contributions in and outside of Denishawn

Aura Tavares: Denishawn

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Denishawn, the school and company

• What is the significance and how did it influence the development of modern dance?

Performance piece for the group: Either learn from video or create a 1 min solo that Denishawn could have performed, and danced in costume.

Martha Graham

Ivana Rodrigues

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Influence of Louis Horst on her

• The essence of her technique

Stephone Nicholas

Writing/speaking prompt:

• The major characteristics of her dance in terms of what were her dances about.

• Some of her choreographic devices

Takiya Richardson

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Her collaboration with other artists

• Why is Martha Graham such an icon in modern dance?

Performance piece for the group: Perform a 1 min segment from Martha Graham’s work. Music provided: Appalachian Spring.

Humphrey/Weidman: Doris Humphrey & Charles Weidman

Taylor Oliveira

Writing/speaking prompt:

• The American dance that Humphrey/Weidman set out to create

• The essence of Humphrey/Weidman technique

Rachel Klein

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Doris Humphrey’s ideas about dance

• Her major contributions

Phania Exavier

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Charles Weidman’s unique style in choreography

Performance piece for the group: Water Study. No music required, just breathe. Wear unitard or leotards & tights in water color

Jose Limon

Brett Bell

Writing/speaking prompt:

• His connection to Doris Humphrey and how he continued the lineage.

Bianca Distefano

Writing/speaking prompt;

• Jose Limon as a performer

• Characteristics of his choreography

Performance piece for the group: 1 min segment from There is a Time. Music provided.

Paul Taylor

Karen Cedant:

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Paul Taylor’s background before he became a dancer, and his training as a dancer

Fedner Dorrelus:

Writing/speaking prompt:

• The characteristics and range of choreography created by Paul Taylor

Gabriela Silva:

Writing/speaking prompt:

• Tayor’s connection to Martha Graham

• Is he a follower or rebel?

Performance piece for the group: 1 min segment from Esplande. Music: Bach’s concerto . Dance dresses and leotard and pants.

Merce Cunningham = Ms Chan

Chance Choreography: performed by the entire class

Tuesday, December 18, 2007

Monday, December 17, 2007

Paul Taylor

Paul Taylor

1930 -

One never knows quite what to expect of Paul Taylor. His choreography keeps slipping unpredictably from style to style and theme to theme.

His father was a physicist; his mother managed a dining room in a Washington, D.C. hotel, and they divorced when he was young. Taylor, who was born in 1930, was attracted to both art and athletics. As a student at the University of Syracuse, he was asked to serve as partner in a program by the campus modern dance club. That so whetted his interest in dance that he finally summoned the courage to tell his athletic coach that he wished to become a professional dancer. The coach proved more sympathetic to dance than Ted Shawn's fraternity brothers had been. "Kiddo," he said, "you sound like you've gone bonkers, but I guess there's no stopping you."

Taylor studied dance at Juilliard and performed with the companies of Cunningham and Graham. When Graham and George Balanchine collaborated on Episodes in 1958, Balanchine created a solo especially for Taylor. In the mid-1950S, Taylor began offering his own programs. Much of his early choreography was whimsical or eccentric. Typically, Three Epitaphs (a 1960 revision of a 1956 piece called Four Epitaphs) depicted bizarre creatures totally encased in black costumes designed by Robert Rauschenberg who slouched and loped to recordings of old New Orleans funeral music in a manner that was simultaneously funny, grotesque, and endearing.

A 1957 concert by Taylor left one distinguished dance critic totally speechless. The entire program was based on walking and running steps and simple, but significant, changes of position. In Epic, Taylor, neatly attired in a business suit, slowly moved and paused and resumed his steps to recorded time signals. Duet, for Taylor and Toby Glanternik, involved held positions: Taylor remained standing and Glanternik remained sitting throughout the piece-and that was the entire dance. The uncompromising simplicity of these works so befuddled Louis Horst that his review for Dance Observer consisted of nothing but a blank space with his initials at the bottom of it.

Although Taylor reveled in absurdity, he soon demonstrated that his choreographic personality was split in several ways. His Aureole (1962) surprised dancegoers not with its oddity, but with its lyricism, and this dance to the music of Handel became one of Taylor's most popular creations. Its serene joy has even struck some audiences as balletic. However, its resemblance to ballet is superficial, and when Taylor stages Aureole for ballet companies, he finds that members of these troupes often find it difficult, for the choreography abounds with "unclassical" swings of the arms and jutting hips; moreover, whereas many ballets require their dancers to take lightness for granted, the dancers in Aureole are made to appear weighted bodies which achieve lightness.

Because of its sheer diversity, Taylor's work has come to epitomize the pluralism of modern dance since the 1960S. Taylor himself ignores all restrictive compositional theories. For him, as he put it, "There are no rules, just decisions."

Of all the American modern choreographers since Graham, it is Taylor who has developed the most diverse repertoire for his company. He tries to make each new work have a form, a style, and what could be called a movement palette uniquely its own.

Many of his most popular creations-among them, Airs (1978) and Arden Court (1981)-are genial. Pleasant to behold, they can at the same time be stimulating to think about because of the compositional principles on which they are built. Thus Arden Court is undeniably lyrical. But Taylor achieves lyricism not by emphasizing graceful steps for women, as some choreographers might do, but by stressing the male dancers in the cast. Taylor makes the men move with great speed, but the overall effect is idyllic, rather than purely athletic.

Taylor is a moralist as well as an entertainer. In serious and humorous works alike, he grapples with the problem of how to achieve a golden mean in life, and he deplores extreme behavior of any kind, be it puritanical or licentious. In Big Bertha (1971), members of a seemingly ordinary family are driven to violence and sexual depravity by an alluring, yet menacing, automaton. The apparently elegant people of Cloven Kingdom (1976) shed their fine manners and behave like beasts. Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal )- Taylor's disquieting interpretation of Stravinsky- is simultaneously a detective story about gangsters and a kidnapped baby and a peek into the backstage life of a dance company rehearsing a detective-story ballet. Because Taylor deliberately fails to supply motivation for many of the startling events in his Sacre, this work of 1980 can be viewed as a choreographic depiction of life at its most irrational and inexplicable.

Taylor remains fascinated by the ambiguities of movement. Esplanade (1975) is made up of nothing but such ordinary actions as walking, running, sliding, falling, and jumping. But these commonplace steps are taken to virtuoso extremes: only trained dancers can walk and run with such ease and abandon. In Polaris (1976), Taylor offers the same dance twice with no choreographic changes whatsoever. Yet each presentation of this basic dance has different lighting designs and is performed by a different cast to different music by Donald York-and the effect each time is totally dissimilar. Taylor knows how to please the eye and how to test his audience's powers of perception.

Lester Horton

Lester Horton

Lester Horton was a choreographic individualist on the West Coast and did not bring his Los Angeles company to New York until shortly before his death in 1953. Born in 1906, Horton studied art and ballet and became involved in little theatre activities in his native Indianapolis. American Indian culture fascinated him, and in 1928 he was invited to California to stage a pageant based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Song of Hiawatha. As a young Bohemian, Horton kept his hair long and bushy and favored Indian shirts and huaraches. He directed plays and pageants and worked with Michio Ito, then organized his own Lester Horton Dancers in 1932.

Horton explored the black, Chinese, Japanese, and Mexican communities of Los Angeles and made friends in all of these districts. He staged dances on Mexican, Haitian, and American Indian themes. He also choreographed his own version of Le Sacre du Printemps in 1937. One dramatic subject that obsessed him all his life was the story of Salome. He created his first Salome in 1934; other versions followed in later years, one under the title Face of Violence. Under any title, Salome was forceful and macabre.

Also in 1934, Horton began his association with Bella Lewitzky, a strikingly dramatic performer who for the next fifteen years served as his choreographic guinea pig and leading lady. Together, they began to develop a systematized plan of teaching, laying the groundwork of what came to be known as "Horton technique."

Just as modern dancers often took work in the commercial theatre in order to earn money, so Horton's dancers appeared ill stage shows and Hollywood films. Horton struggled to make ends meet. Yet he managed to survive and, by doing so, he demonstrated that New York did not have to be the only home for modern dance in America.

Until his death in 1953, Lester Horton remained active in Los Angeles. His later works included further revisions of Salome, as well as The Beloved, a savage portrait of a stern, religiously bigoted husband who kills his wife when he suspects her of infidelity. Horton welcomed dancers of all races into his company and, a generous man, offered a multitude of scholarships. Among the dancers who worked with him in the years before his death were Alvin Ailey, Carmen de Lavallade, Joyce Trisler, and James Truitte.

Excerpted from Art Without Boundaries: The World of Modern Dance

By Jack Anderson

Merce Cunningham (a)

Merce Cunningham

1919 -

Merce Cunningham's innovations have been especially controversial and influential. Born in Centralia, Washington, in 1919, he began to study dance locally at the age of twelve. Intending to become an actor, he enrolled at the Cornish School in Seattle, where he was encouraged to dance by Bonnie Bird, a former member of the Graham Company who was on the Cornish faculty. There he also met John Cage, a young experimental composer. Together, Cunningham and Cage developed unconventional ideas of dance composition.

Committed to a dance career, Cunningham attended Bennington's 1939 session at Mills College in Oakland, California, where he attracted the attention of Martha Graham. After moving to New York, he danced with her company, 1939-1945, and presented his first New York choreography in 1942 in a concert he shared with Jean Erdman and Nina Fonaroff. He also toured as a dance soloist in musical programs by Cage. After 1945, he devoted himself full-time to his own choreography, with Cage serving as his artistic adviser.

Cunningham could be dramatically forceful as a performer, both in the Graham repertory and in his own early pieces. In 1945, Robert Sabin of Dance Observer called Experiences "the most gripping thing" Cunningham had done and found that it "marks a new advance in dramatic realization. Its ferocity and body dynamics, its 'freezes' (in which the movement is suddenly arrested with tremendous effect) are not only exciting as examples of virtuosity but they show a spirit of creative experimentation which promises well for the future." In that same review, Sabin noted that Cunningham was blessed with a sense of humor and found his Mysterious Adventure "deliciously impish in flavor."

Cunningham continued to receive praise for his dramatic presence and whimsical comedy. But he put these qualities to unconventional use. Even at the beginning of his career, he stood apart from many of his choreographic colleagues. Reviewing a 1944 concert, Sabin presciently observed that the event was unusual for its "pure, unadulterated dancing. ...He is a classicist (if one may venture to use that dangerous word) in the sense that he absolutely believes in dance as an independent medium of expression with its own laws and objectives."

Printed programs for Cunningham's concerts often included this credo: "Dancing has a continuity of its own that need not be dependent upon either the rise and fall of sound, or the pitch and cry of words. Its force of feeling lies in the physical image, fleeting or static.

It can and does evoke all sorts of individual responses in the single spectator." Cunningham's dances were plotless. Nevertheless, they were perceived as having their own special choreographic personalities and atmospheres, possibly because the specific kinds of movements he favored in each prompted similar reactions in the-audiences that beheld them. Thus, no one ever called Cunningham's harsh Winterbranch sweet or his lyrical Summerspace savage.

Cunningham often commissioned new music, and his designers over the years included such eminent artists as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, and Andy Warhol. Yet he made no attempt to have dance phrases coincide with musical phrases and the decor for his dances never literally illustrated anything in them. In 1959, when he choreographed Septet to an existing score-Erik Satie's "Trois Morceaux en Forme de Poire"-some audiences were startled by Cunningham's treatment of the music-as, for instance, in moments when dancers stood perfectly still to loud chords that might have inspired other choreographers to devise passages of frantic activity. Cunningham has said, "It is hard for many people to accept that dancing has nothing in common with music other than the element of time and the division of time." In his productions, dancing, music, and stage design do not provide one another with mutual support; rather, they coexist.

Cunningham came to believe that any space can be danced in and that any point in space can be of interest. For him, stage space was an empty field. He therefore ignored traditional theories of stage direction that maintain that stage center is "strong," whereas movements at the sides of the stage may be "weak."

Just as any point in space can be significant, so, for Cunningham, any movement, however fancy or ordinary, can serve as a dance movement. This theory paralleled John Cage's belief that any sound can be used in a piece of music. Concertgoers found many of the sounds in Cage's early works beguiling, for he explored the possibilities of what he called the prepared piano: a piano with objects carefully placed upon its strings so as to alter their customary timbres. Cage's prepared pianos reminded audiences of unconventionally tuned harpsichords or Balinese gamelans. But as Cage continued his experiments, he alienated some listeners with electronic scores that were found loud, harsh, and grating. The music he composed for

Cunningham's Aeon outraged dancegoers at its premiere at the American Dance Festival in 1961. It "ran its fingernails over our eardrums," Doris Hering complained, and Louis Horst dismissed it as "shattering and ear-splitting noise." A scientist in the "audience even announced, "The sound level in that auditorium is dangerous for human ears."

Whatever sounds may have accompanied them, Cunningham's choreographic phrases were so lucid that his style was sometimes compared with ballet. Nevertheless, despite what could be called his “classical" tendencies, his choreography was often controversial. His theories regarding chance and indeterminacy helped make it so. These words bewilder some dancegoers, who regard them as synonyms for improvisation. But Cunningham's choreography is not improvised; his dancers do not invent their steps as they go along. Indeed, if he had not publicly announced that he employed chance in making some works, spectators might not even suspect that he had done so.

Cunningham first employed chance in 1951 when he choreographed Sixteen Dances for Soloist and Company of Three, a work inspired by the Indian theatre's nine traditional categories of human emotions. Unable to decide which emotion should follow which onstage, Cunningham threw a coin to determine the order; but once that order was established, it remained unaltered. For Suite by Chance (1953), he prepared elaborate charts of possible movements, then selected the specific ones to be employed by tossing coins. If he had not said that he had done so, few (if any) spectators could have guessed it.

In contrast, effects of indeterminacy can be visible in the theatre- provided one sees more than a single performance of a given dance. In indeterminate compositions, the choreographer or the dancers can alter the order of sequences or omit some of them at each performance. But, once again, they do not have the freedom to improvise. Although Cunningham devised thirteen brief dances for his suite Dime a Dance (1953), only eight of them were ever presented on any night. The cast members of Field Dances (1963) were assigned a specific number of things to do, but were left free to do them at whatever speed they chose, as often as they wished, and in any order.

Cunningham's fascination with chance and indeterminacy had historical precedents, for the Dadaists and Surrealists had made use of chance. Like them, Cunningham believes that most people too easily become creatures of habit. Through chance, however, artists can discover images or patterns that their purely rational minds might not have invented. Chance also allows creators to ignore or transcend conventional cause-and-effect logic. Chance leaves room for surprise.

From Art without boundaries: The World of Modern Dance

By Jack Anderson

1919 -

Merce Cunningham's innovations have been especially controversial and influential. Born in Centralia, Washington, in 1919, he began to study dance locally at the age of twelve. Intending to become an actor, he enrolled at the Cornish School in Seattle, where he was encouraged to dance by Bonnie Bird, a former member of the Graham Company who was on the Cornish faculty. There he also met John Cage, a young experimental composer. Together, Cunningham and Cage developed unconventional ideas of dance composition.

Committed to a dance career, Cunningham attended Bennington's 1939 session at Mills College in Oakland, California, where he attracted the attention of Martha Graham. After moving to New York, he danced with her company, 1939-1945, and presented his first New York choreography in 1942 in a concert he shared with Jean Erdman and Nina Fonaroff. He also toured as a dance soloist in musical programs by Cage. After 1945, he devoted himself full-time to his own choreography, with Cage serving as his artistic adviser.

Cunningham could be dramatically forceful as a performer, both in the Graham repertory and in his own early pieces. In 1945, Robert Sabin of Dance Observer called Experiences "the most gripping thing" Cunningham had done and found that it "marks a new advance in dramatic realization. Its ferocity and body dynamics, its 'freezes' (in which the movement is suddenly arrested with tremendous effect) are not only exciting as examples of virtuosity but they show a spirit of creative experimentation which promises well for the future." In that same review, Sabin noted that Cunningham was blessed with a sense of humor and found his Mysterious Adventure "deliciously impish in flavor."

Cunningham continued to receive praise for his dramatic presence and whimsical comedy. But he put these qualities to unconventional use. Even at the beginning of his career, he stood apart from many of his choreographic colleagues. Reviewing a 1944 concert, Sabin presciently observed that the event was unusual for its "pure, unadulterated dancing. ...He is a classicist (if one may venture to use that dangerous word) in the sense that he absolutely believes in dance as an independent medium of expression with its own laws and objectives."

Printed programs for Cunningham's concerts often included this credo: "Dancing has a continuity of its own that need not be dependent upon either the rise and fall of sound, or the pitch and cry of words. Its force of feeling lies in the physical image, fleeting or static.

It can and does evoke all sorts of individual responses in the single spectator." Cunningham's dances were plotless. Nevertheless, they were perceived as having their own special choreographic personalities and atmospheres, possibly because the specific kinds of movements he favored in each prompted similar reactions in the-audiences that beheld them. Thus, no one ever called Cunningham's harsh Winterbranch sweet or his lyrical Summerspace savage.

Cunningham often commissioned new music, and his designers over the years included such eminent artists as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, and Andy Warhol. Yet he made no attempt to have dance phrases coincide with musical phrases and the decor for his dances never literally illustrated anything in them. In 1959, when he choreographed Septet to an existing score-Erik Satie's "Trois Morceaux en Forme de Poire"-some audiences were startled by Cunningham's treatment of the music-as, for instance, in moments when dancers stood perfectly still to loud chords that might have inspired other choreographers to devise passages of frantic activity. Cunningham has said, "It is hard for many people to accept that dancing has nothing in common with music other than the element of time and the division of time." In his productions, dancing, music, and stage design do not provide one another with mutual support; rather, they coexist.

Cunningham came to believe that any space can be danced in and that any point in space can be of interest. For him, stage space was an empty field. He therefore ignored traditional theories of stage direction that maintain that stage center is "strong," whereas movements at the sides of the stage may be "weak."

Just as any point in space can be significant, so, for Cunningham, any movement, however fancy or ordinary, can serve as a dance movement. This theory paralleled John Cage's belief that any sound can be used in a piece of music. Concertgoers found many of the sounds in Cage's early works beguiling, for he explored the possibilities of what he called the prepared piano: a piano with objects carefully placed upon its strings so as to alter their customary timbres. Cage's prepared pianos reminded audiences of unconventionally tuned harpsichords or Balinese gamelans. But as Cage continued his experiments, he alienated some listeners with electronic scores that were found loud, harsh, and grating. The music he composed for

Cunningham's Aeon outraged dancegoers at its premiere at the American Dance Festival in 1961. It "ran its fingernails over our eardrums," Doris Hering complained, and Louis Horst dismissed it as "shattering and ear-splitting noise." A scientist in the "audience even announced, "The sound level in that auditorium is dangerous for human ears."

Whatever sounds may have accompanied them, Cunningham's choreographic phrases were so lucid that his style was sometimes compared with ballet. Nevertheless, despite what could be called his “classical" tendencies, his choreography was often controversial. His theories regarding chance and indeterminacy helped make it so. These words bewilder some dancegoers, who regard them as synonyms for improvisation. But Cunningham's choreography is not improvised; his dancers do not invent their steps as they go along. Indeed, if he had not publicly announced that he employed chance in making some works, spectators might not even suspect that he had done so.

Cunningham first employed chance in 1951 when he choreographed Sixteen Dances for Soloist and Company of Three, a work inspired by the Indian theatre's nine traditional categories of human emotions. Unable to decide which emotion should follow which onstage, Cunningham threw a coin to determine the order; but once that order was established, it remained unaltered. For Suite by Chance (1953), he prepared elaborate charts of possible movements, then selected the specific ones to be employed by tossing coins. If he had not said that he had done so, few (if any) spectators could have guessed it.

In contrast, effects of indeterminacy can be visible in the theatre- provided one sees more than a single performance of a given dance. In indeterminate compositions, the choreographer or the dancers can alter the order of sequences or omit some of them at each performance. But, once again, they do not have the freedom to improvise. Although Cunningham devised thirteen brief dances for his suite Dime a Dance (1953), only eight of them were ever presented on any night. The cast members of Field Dances (1963) were assigned a specific number of things to do, but were left free to do them at whatever speed they chose, as often as they wished, and in any order.

Cunningham's fascination with chance and indeterminacy had historical precedents, for the Dadaists and Surrealists had made use of chance. Like them, Cunningham believes that most people too easily become creatures of habit. Through chance, however, artists can discover images or patterns that their purely rational minds might not have invented. Chance also allows creators to ignore or transcend conventional cause-and-effect logic. Chance leaves room for surprise.

From Art without boundaries: The World of Modern Dance

By Jack Anderson

Alwin Nikolais

EXCERPTS FROM "NIK: A DOCUMENTARY"

My total theater concept consciously started about 1950, although the seeds of it began much earlier I'm sure. First was expansion. I used masks and props-the masks, to have the dancer become something else; and props, to extend his physical size in space. (These latter were not instruments to be used as shovels or swords-but rather as extra bones and flesh.) I began to see the potentials of this new creature and in 1952 produced a program called Masks Props & Mobiles. I began to establish my philosophy of man being a fellow traveler within the total universal mechanism rather than the god from which all things flowed. The idea was both humiliating and aggrandizing. He lost his domination but instead became kinsman to the universe.

* * *

Dancers often get into the pitfall of emotion rather than motion. To me motion is primary-it is the condition of motion which culminates into emotion. In other words it is our success or failure in action in time and space which culminates in emotion. This drama of action is universally understood by Chinese, Africans, South Americans and the Zulus. We do not have to be educated to understand the abstract language of motion, for motion is the stuff with which our every moment of life is preciously concerned. So in the final analysis the dancer is a specialist in the sensitivity to, the perception and the skilled execution of motion. Not movement but rather the qualified itinerary en route. The difference may be made even clearer by giving the example of two men walking from Hunter College to 42nd and Broadway. One man may accomplish it totally unaware of and imperceptive to the trip, having his mind solely on the arrival. He has simply moved from one location to another. The other may, bright-eyed and bright-brained, observe and sense all thru which he passes. He has more than moved-he is in motion.

* * *

From The Vision of Modern Dance: In the Words of Its Creators

Edited by Jean Morrison Brown, Naomi Mindlin & Charles H. Woodford

Alwin Nikolais

1910-1993

Alwin Nikolais has been called choreography's Wizard of Oz. Nikolais himself said he was a choreographic polygamist because he sought "a polygamy of motion, shape, color, and sound." Whatever one called him, he was a creator of a multimedia form that made dazzling use of theatrical illusion.

Nikolais (1912-1993) was born in Southington, Connecticut, and as a young man worked as a puppeteer and as a pianist for silent films. A performance by Mary Wigman made him want to study with one of her disciples-but not primarily to learn dance. Rather, he was intrigued by her use of percussion instruments. He found a Wigman-trained teacher, Truda Kaschmann, in Hartford. His love of dance soon equaled his love of music, and he studied at the Bennington summer schools, where he was particularly impressed by Hanya Holm's teaching. After military service in World War II, he became her assistant.

In 1948, he joined the staff of the Henry Street Settlement Playhouse-the former Neighborhood Playhouse-and it remained his base until the late 196os, when he found larger quarters necessary. He turned the tiny Henry Street Playhouse into a magician's box of marvels. Playing theatrical conjuring tricks, he not only choreographed his productions, but also designed scenery, costumes, and lighting and composed their electronic scores.

Nikolais transformed the appearance of dancers by encasing them in fantastic constructions or by attaching sculptural shapes to their bodies. He also flooded dancers with changing light patterns so as to blur distinctions between illusion and reality and make it difficult for spectators to determine which shapes before them were real and which were shadows or slide projections. Nikolais's use of technology made him an artistic heir of Lole Fuller and Oskar Schlemmer.

Masks, Props and Mobiles (1953), Nikolais's first major multimedia effort, has a much-praised episode in which dancers encased in bags stretch themselves into odd shapes as they move. The shape of dancing bodies in Kaleidoscope (1962) was altered with the aid of discs, poles, paddles, hoops, straps, and capes. Nikolais subtitled Imago (1963) "The City Curious," and its inhabitants included scurrying robotlike figures, men with fantastically long arms who are hooked together as if in a giant chain, and men and women who move between lines of elastic tape stretched from one side of the stage to the other. At various points in Sanctum (1964), dancers had to swing from a trapeze, manipulate silver poles, and struggle to escape from enclosures that kept changing size.

Some of Nikolais's productions can be enjoyed simply as abstract studies in motion. Others possess thematic implications: the way a tower explodes after dancers have struggled to erect it in Tower (1965) brings to mind the biblical story of the Tower of Babel, and with the aid of slide projections Nikolais makes dancers resemble water plants and creatures in Pond (1982).

Echoing complaints once brought against Schlemmer, Nikolais's detractors contended that he dehumanized dancers. But George Beiswanger defended Nikolais's choreographic approach by pointing out that Nikolais "wants things to move, to be seen, and to be heard, and he wants the resulting aliveness of things to be apparent even when the things are dancers. Hence the props dance and the dancers prop (not that they do not dance as well). Now one may take this in two ways, as dehumanizing the dancer or as animizing the thing. I am inclined, perhaps perversely, to the latter view." 16 It can also be argued that, by uniting dancers with scenic effects, Nikolais choreographically expressed ecological concerns and that the harmonious or contentious encounters between dancers and objects are parables of ways in which people interact with their environment in the real world.

However one interprets them, Nikolais's productions are almost always entertaining. He not only resembles the Wizard of Oz, he is also akin to the Wizard's creator, L. Frank Baum, that lover of peculiar animated gadgets. Nikolais himself once admitted, "I am a compulsive creator-if you gave me a schnauzer, two Armenian chastity belts and a 19th-century dish pan-I would attempt to create something with them."

In addition to training dancers, the Nikolais studio has encouraged choreographers-among them Murray Louis and Phyllis Lamhut. Each has performed with the Nikolais company as well as in each other's works.

Louis, who was born in 1926, began his dance studies with Anna Halprin in San Francisco after military service during World War II. Back in his native New York, he became Nikolais's artistic associate in 1949 and has headed his own successful company, which on several occasions merged with that of Nikolais.

A remarkable virtuoso, Louis can isolate parts of his body and make his limbs move in various, even seemingly contradictory, ways, as if each had a will of its own. His less successful choreography can sometimes appear unduly twitchy. But when he is at his creative best, his dancing and that of his company can be precise and expertly timed, especially to comic effect.

Among his most acclaimed comic pieces are Junk Dances (1964), a portrait of a husband and wife (Louis and Lam hut) surviving marital vicissitudes in what can be interpreted either as a literal junkyard or a theatrical metaphor for an emotional trashpile, and Hoopla (1973), a tribute to circus acts. His works also extend from the somber all-male Calligraph for Martyrs (1961) to the lyrical Porcelain Dialogues (1974).

Lam hut, who was born on Manhattan's Lower East Side in 1933, received her early dance training at the Henry Street Settlement; although she has studied elsewhere, she has remained closely associated with Nikolais and Louis, as well as with the Hanya Holm Studio.

She first attracted attention as a deft comedienne, then expanded her scope to create large-scale ensembles with some of the fervor of the German Ausdruckstanz.

From Art Without Boundaries: The World of Modern Dance

By Jack Anderson

Merce Cunningham

Space, Time and Dance, 1952

The dance is an art in space and time.

The object of the dancer is to obliterate that.

The classical ballet, by maintaining the image of the Renaissance perspective in stage thought, kept a linear form of space. The modern American dance, stemming from German expressionism and the personal feelings of the various American pio¬neers, made space into a series of lumps, or often just static hills on the stage with actually no relation to the larger space of the stage area, but simply forms that by their connection in time made a shape. Some of the space-thought coming from the German dance opened the space out, and left a momentary dealing of con¬nection with it, but too often the space was not visual enough because the physi¬cal action was all of lightness, like sky without earth, or heaven without hell.

The fortunate thing in dancing is that space and time cannot be disconnected, and everyone can see and understand that. A body still is taking up just as much space and time as a body moving. The result is that neither the one nor the other-moving or being still-is more or less important, except it's nice to see a dancer moving. But the moving becomes more clear if the space and time around the moving are one of its opposite-stillness. Aside from the personal skill and clarity of the individual dancer, there are certain things that make clear to a spectator what the dancer is doing. In the ballet the various steps that lead to the larger movements or poses have, by usage and by their momentum, become common ground upon which the spectator can lead his eyes and his feelings into the resulting action. This also helps define the rhythm, in fact more often than not does define it. In the modern dance, the tendency or the wish has been to get rid of these "unnecessary and balletic" movements, at the same time wanting the same result in the size and vigor of the movement as the balletic action, and this has often left the dancer and the spectator slightly short.

To quibble with that on the other side: one of the best discoveries the modern dance has made use of is the gravity of the body in weight, that is, as opposite from denying (and thus affirming) gravity by ascent into the air, the weight of the body in going with gravity, down. The word "heavy" connotes something incorrect, since what is meant is not the heaviness of a bag of cement falling, although we've all been spectators of that too, but the heaviness of a living body falling with full intent of eventual rise. This is not a fetish or a use of heaviness as an accent against a pre¬dominately light quality, but a thing in itself. By its nature this kind of moving would make the space seem a series of unconnected spots, along with the lack of clear-connecting movements in the modern dance.

A prevalent feeling among many painters that lets them make a space in which anything can happen is a feeling dancers may have too. Imitating the way nature makes a space and puts lots of things in it, heavy and light, little and big, all unrelated, yet each affecting all the others.

About the formal methods of choreography-some due to the conviction that a communication of one order or another is necessary; others to the feeling that mind follows heart, that is, form follows content; some due to the feeling that the musical form is the most logical to follow-the most curious to me is the general feeling in the mod¬ern dance that nineteenth-century forms stemming from earlier pre-classical forms are the only formal actions advisable, or even possible to take. This seems a flat contradiction of the modern dance-agreeing with the thought of discover¬ing new or allegedly new movement for contemporary reasons, the using of psy¬chology as a tremendous elastic basis for content, and wishing to be expressive of the "times" (although how can one be expressive of anything else)-but not feel¬ing the need for a different basis upon which to put this expression, in fact being mainly content to indicate that either the old forms are good enough, or further that the old forms are the only possible forms. These consist mainly of theme and variation, and associated devices-repetition, inversion, development, and manipulation. There is also a tendency to imply a crisis to which one goes and then in some way retreats from. Now I can't see that crisis any longer means a climax, unless we are willing to grant that every breath of wind has a climax (which I am), but then that obliterates climax, being a surfeit of such. And since our lives, both by nature by the newspapers, are so full of crisis that one is no longer aware of it, then it is clear that life goes on regardless, and further that each thing can be and is separate from each other, viz: the continuity of the newspa¬per headlines. Climax is for those who are swept by New Year's Eve.

More freeing into space that the theme and manipulation "holdup" would be formal structure based on time. Now time can be an awful lot of bother with the ordinary pinch¬penny counting that has to go on with it, but if one can think of the structure as a space of time in which anything can happen in any sequence of movement event, and any length of stillness can take the place, then the counting is an aid towards freedom, rather than a discipline towards mechanization. A use of time¬-structure also frees the music into space, making the connection between the dance and the music one of individual autonomy connected at structural points. The result is the dance is free to act as it chooses, as is the music. The music does¬n't have to work itself to death to underline the dance, or the dance create havoc in trying to be as flashy as the music.

For me, it seems enough that dancing is a spiritual exercise in physical form, and that what is seen, is what it is. And I do not believe it is possible to be "too simple." What the dancer does is the most realistic of all possible things, and to pretend that a man standing on a hill could be doing everything except just standing is simple divorce-divorce from life, from the sun coming up and going down, from clouds in front of the sun, from the rain that comes from the clouds and sends you into the drugstore for a cup of coffee, from each thing that succeeds each thing. Dancing is a visible action of life.

Merce Cunningham

Four Events That Have Led to Large Discoveries, 1994

During the course of working in dance, there have been four events that have led to large discoveries in my work.

The first came with my initial work with John Cage, early solos, when we began to separate the music and the dance. This was in the late forties. Using at that time what Cage called a "rhythmic structure"-the time lengths that were agreed upon as beginning and ending structure points between the music and the dance¬ - we worked separately on the choreography and the musical composition. This allowed the music and the dance to have an independence between the struc¬ture points. From the beginning, working in this manner gave me a feeling of freedom for the dance, not a dependence upon the note-by-note procedure with which I had been used to working. I had a clear sense of both clarity and interdependence between the dance and the music.

The second event was when I began to use chance operations in the choreography, in the fifties. My use of chance procedures is related explicitly to the choreography. I have utilized a number of different chance operations, but in principle it involves working out a large number of dance phrases, each separately, then applying chance to discover the continuity-what phrase follows what phrase, how time-wise and rhythmically the particular movement operates, how many and which dancers might be involved with it, and where it is in the space and how divided. It led, and continues to lead, to new discoveries as to how to get from one movement to the next, presenting almost constantly situations in which the imagination is challenged. I continue to utilize chance operations in my work, finding with each dance new ways of experiencing it.

The third event happened in the seventies with the work we have done with video and film. Camera space presented a challenge. It has clear limits, but it also gives opportunities of working with dance that are not available on the stage. The camera takes a fixed view, but it can be moved. There is the possibility of cutting to a second camera which can change the size of the dancer, which, to my eye, also affects the time, the rhythm of the movement. It also can show dance in a way not always possible on the stage: that is, the use of detail which in the broad context of theater does not appear. Working with video and film also gave me the opportunity to rethink certain technical elements. For example, the speed with which one catches an image on the television made me introduce into our class work different elements concerned with tempos which added a new dimension to our general class work behavior.

The fourth event is the most recent. For the past five years, I have had the use of a dance computer, Life Forms, realized in a joint venture between the Dance and Science departments of Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. One of its uses is as a memory device: that is, a teacher could put into the memory of the computer exercises that are given in class, and these could be looked at by students for clarification. I have a small number of particular exercises we utilize in our class work already in the memory. But my main interest is, as always, in discovery. With the figure, called the Sequence Editor, one can make up movements, put them in the memory, eventually have a phrase of move¬ment. This can be examined from any angle, including overhead, certainly a boon for working with dance and camera. Furthermore, it presents possibilities which were always there, as with photos, which often catch a figure in a shape our eye had never seen. On the computer the timing can be changed to see in slow motion how the body changes from one shape to another. Obviously, it can produce shapes and transitions that are not available on humans, but as happened first with the rhythmic structure, then with the use of chance operations, followed by the use of the camera on film and video and now with the dance computer, I am aware once more of new possibilities with which to work

My work has always been in process. Finishing a dance has left me with the idea, often slim in the beginning, for the next one. In that way, I do not think of each dance as an object, rather a short stop on the way.

Merce Cunningham

Thursday, December 13, 2007

Modern Dance History

Modern Dance History

European Perspective

Brief History:

Although often considered an American phenomenon, the evolution of modern dance can also be traced to Central Europe and Germany where the most influential person was probably Rudolf von Laban He is generally acknowledged as the founder of modern dance theory. His great contribution lay in developing a systematic analysis of human movement in time and space that lead to a coherent system of dance notation known as kinetography or Labanotation. He championed Dance Movement Therapy and formulated theories on educational dance and studies of time and motion in relation to industrial production.

Although there is almost no documentation to describe his choreography, he founded (1910) a school in Munich. Exiled in the 1930s, he emigrated to England where he established (1946) the Art of Movement Studio in Manchester. Laban worked until his death on his system of notation.

One of Laban's most celebrated students and associates was MARY WIGMAN. She enjoyed fame as a choreographer and performer in the period between the two World Wars. She began studying dance under Rudolf Laban in 1913. Mary Wigman wanted to establish the independence of dance as an art form and began by divorcing dance from its dependence on music. Her work had great expressive force. After studying with Laban Wigman performed in Germany and opened her own school in Dresden (1920). She became the most influential German exponent of expressive movement and toured extensively. Her school was closed by the Nazis but she reopened it in Berlin in 1948.

HANYA HOLM was a student of Mary Wigman and a teacher at the Wigman School in Dresden. In 1931 Holm founded the New York School of Dance. She introduced the Wigman technique to American modern dance, as well as Laban's theories. She was herself an accomplished choreographer. Her dance work "Metropolitan Daily" was the first modern dance composition to be copyrighted in the United States. Holm choreographed extensively in the fields of concert dance and musical theatre.

KURT JOOSS was also part of this Central European dance movement and formed together with SIGRID LEEDER, the Ballets Jooss. "The Green Table" (1932) was an Expressionist vision of the horrors of war which contained a famous scene of masked diplomats negotiating round the Green Table. He abandoned straight storytelling in favour of a variety of themes loosely interconnected. Like Laban he had to flee Hiltlers Germany.

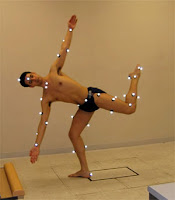

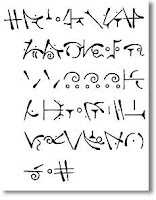

L = Left side

C = Centerlinie

R = Right side

1 = Support column

2 = Leg gesture column

3 = Body column

4 = Arm column

5 = Head column

There are nine horizontal direction symbols derived from the rectangle.

P = Place

F = Forward

B = Backward

L = Left

R = Right

LF = Left forward

RF = Right forward

LB = Left backward

RB = Right backward

Labanotation figures

Mary Wigman’s Philosophy about dance:

LIKE THE BEST OF THE GERMAN EXPRESSIONIST PAINTERS, many German modern dancers realized that feelings could not be communicated to other people simply through emotional outpouring. The dancers and the painters alike believed that art is most powerful when form and content are inseparably joined.

Scores of dance lovers of the 192O’s and early 193O’s considered the works of Mary Wigman to be among the most memorable examples of such a union. Wigman loved to say, "Without ecstasy there is no dance. Without form there is no dance." For Wigman, form was not merely a container for ecstasy (or for any other passion or idea), but its very embodiment, and her ability to externalize feelings made her one of the greatest choreographers of the twentieth century.

Often expressionistic, her works ranged from gentle dances of nature to the macabre. She believed that “art grows out of the basic cause of existence. "

Characteristics of Wigman’s work:

Several aspects of Wigman's productions prompted comment. One was her use-or nonuse-of music. Some of her dances were performed in silence. Others did have music. But to assert the autonomy of dance as an art, Wigman's accompaniments were composed by musicians along with the choreography or entirely after the choreography had been created. Her scores were often spare and were intended to be of no artistic interest apart from the dances for which they were written. They also made extensive use of percussion instruments. For her 1931 American tour, Wigman brought over two Hungarian flutes, an assortment of drums, five Chinese gongs, one set of Indian bells, and a pair of cymbals. The rhythms of such instruments helped call attention to or intensify the choreographic rhythms.

Wigman sometimes danced wearing masks, not merely to look fantastic or bizarre, but in an attempt to escape from or transcend her ordinary self. She made a subtle distinction between makeup and masks: "Makeup gives the dancer's features a second skin and plays along with his finest and most detailed facial expressions. Not so the rigidity of the mask. It preserves its clearly defined contours, its sculptural shape. It gives the dancer a second face, it characterizes and typifies, but can never be exploited psychologically."

Possibly as a result of her training with Laban, Wigman possessed a remarkable awareness of space. She viewed the stage not as a floor to cross, but as a three-dimensional entity with which she could have emotional as well as physical relationships. Hanya Holm, one of her pupils who became a distinguished choreographer and teacher in her own right, has remarked that in Wigman's dances "she alternately grapples with space as an opponent and caresses it as though it were a living, sentient thing."

Hanya Holm (3 March 1893, Worms, Germany – 3 November 1992, New York City) was the professional name of Johanna Eckert, dancer, choreographer, and teacher. Holm was one of the pioneers of modern dance.

Born in Worms, Germany, Holms was a student and assistant of Mary Wigman and instructor at the Wigman School in Dresden. Holm founded the New York Wigman School of Dance in 1931 (which became the Hanya Holm Studio in 1936) introducing the Wigman technique, Laban's theories of spatial dynamics, and later her own dance techniques to American modern dance. After 1974, she taught dance at the Juilliard School in New York.

An accomplished choreographer she was a founding artist of the first American Dance Festival in Bennington (1934). Holm's dance work Metropolitan Daily was the first modern dance composition to be televised on NBC, and her labanotation score for Kiss Me, Kate (1948) was the first choreography to be copyrighted in the United States. She also worked on My Fair Lady (1956), Camelot (1960), and Anya (1965). Holm choreographed extensively in the fields of concert dance and musical theatre.

Her students included Glen Tetley, Alwin Nikolais, and Alvin Ailey.

About her work:

Holm was a petite person with fair skin and blonde hair. There was a distinct delicacy and an expressive lyricism in her dancing. She developed an impressive fleetness and strikingly quick footwork. What also distinguished Holm's dancing was her intimate relationship with music, which strongly motivated her.

Her lecture-demonstrations, which explored the space and tension on which her teaching was based, were almost dreamlike in their lyric molding of space and mood. The distinctive movement of her students had a light and lyric air. Holm knew how to fuse her principles of the old world with the vitality, the energy, the swift spirit of the American dancers.

When she created for the concert stage, her dances were emotional responses to life

Monday, November 19, 2007

THE FOUR PIONEERS

THE FOUR PIONEERS

INTRODUCTION

Called at various times "Papa Shawn" and the "Father of American Dance," Ted Shawn was the kind of parent who required submission and inspired rebellion in his offspring. The first of the famous Denishawn "children" to leave the fold was Martha Graham in 1923. Although Shawn had been her primary teacher and had featured her in his dances, she felt that she must strike out on her own.

The next defectors from Denishawn left in a group in 1928, joining forces for the next sixteen years. Doris Humphrey, star performer and main teacher in the Denishawn school; Charles Weidman, also a performer and teacher there; and Pauline Lawrence, school accompanist, together established the Humphrey-Weidman Dance Company in New York City. These "unholy three" were voted out of Denishawn for dis¬loyalty when Humphrey and Weidman refused to give up their experiments with movement to tour with the Ziegfield Follies. The tour was to raise money for "Greater Denishawn," at that point, a huge, unpaid-for house in the suburbs of New York City.

Shortly before that confrontation, Humphrey had been chided by Shawn for not teaching straight Denishawn tech¬nique in classes. Instead, she had been testing the discoveries she was beginning to make about dance movement.

Paramount among these, and the basis for the technique she was to develop, was her concept that dance takes place in an arc of unbalance, that is the motion which occurs between the ver¬tical (standing) and the horizontal (lying down) positions. This is the basis of the Humphrey Fall and Recovery Theory.

Martha Graham had also begun to develop a new dance technique which continued to evolve out of her choreography during her entire career. The style which she developed was sharp, angular, and percussive; the most distinctive movement, in her technique, the contraction and release involving the torso, resulted from her observations of breathing.

This was the beginning of American modern dance. For the first time American dancers were creating new movements for new subject matter, and reflecting their own era rather than a previous one. Their movements evolved from the meaning of the dance, rather than from previously learned steps developed by peoples of a different culture. In the process of finding new techniques to express their art, these modern dance pioneers broke the existing rules; indeed, that was their intent, for they were anti-Denishawn, anti-ballet, anti-the past.

The percussive, angular, and often distorted movements of early modern dance expressed the tensions of contemporary life. Similar developments in other arts resulted in the Cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque and the dissonant music of Hindemith and Schoenberg. At the same time, dance ceased to be regarded primarily as entertainment, and through the new aesthetics, it achieved the status of a serious, creative, indepen¬dent art form.

All levels of the dancers' space were used, resulting in a rela¬tionship to gravity that was in direct contrast to the danse verti¬cale of the Romantic ballet. The torso became fully active as it was freed of its balletic rigidity, and the dancers angled their limbs, in contrast to the extended line of ballet. Interestingly, many of these movements can be traced to the Denishawn ori¬gins of the pioneers, particularly to the Oriental and Delsartean influences. The difference between the old and the new was that these modern dance originators used the principles they had learned from Denishawn to create new movements. Their first dances accordingly showed a lingering Denishawn influ¬ence, but in time they worked away from it, although their warm-up exercises continued to include a combination of yoga and ballet.

The dancers' costumes and stage settings were extremely simplified, often to the point of starkness. The dance itself was performed either to music written for it by a contemporary composer or to no music at all; occasionally, music of the pre-¬classic or classic period was used. The dancers performed wher¬ever they could: in lofts, studios, and small theaters in New York City, and in colleges and university auditoriums and gymnasi¬ums throughout the country.

Critics played an important role in bringing this avant-garde movement before the public eye and in expanding its small but devoted following. John Martin, a staff critic for The New York Times from 1927 to 1962, had a background in theater but soon began covering modern dance performances extensively, becoming the foremost champion of the fledgling art and the first "dean" of dance critics.

By the time that Louis Horst founded Dance Observer in 1934, he was already an old friend of the modern dancers. As a musician he had accompanied classes and performances at Denishawn. He left in 1925, becoming Martha Graham's advi¬sor, critic, and music composer. In addition, he developed a for¬mal approach to the teaching of dance composition, which has been experienced by countless students over the years. This approach uses art forms and styles from all periods of human history except that in which ballet developed. Dance Observer presented reviews, articles, and advertisements devoted princi¬pally to modern dance, and Horst continued monthly publica¬tion until his death in 1964.

Walter Terry, who studied with Shawn, Graham, Humphrey, Limon, and others, was another critic who supported modern dance through his reviews in the New York Herald-Tribune. Martin, Horst, and Terry have all written definitive books on dance.

In 1931 Hanya Holm came from Germany to open the New York branch of the Mary Wigman School. She had stud¬ied with Dalcroze, Laban, and Wigman before becoming a Wigman company member and teacher. By 1936 she had established the Hanya Holm School and Company, and the New York Wigman School was dissolved. German modern dance, which up to this time had developed parallel to American modern dance, was thus injected into the main¬stream of American modern dance. This dance form, charac¬terized by its use of space and of improvisation as a teaching tool, has retained its uniqueness through the followers of the Laban-Wigman-Holm tradition in this country.

Modern dance coalesced as a movement through the efforts of two far-sighted young women, Martha Hill and Mary Jo Shelly, who established the Bennington College School of the Dance in 1934. There they invited the leading modern dancers to teach and create. Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and Hanya Holm were the permanent faculty from 1934 until its closing in 1941.

The economic stability, the artistic freedom, the space, and the chance to perform gave these four pioneers the opportuni¬ty to focus their energies on the creation of larger works dur¬ing the summer months. Some of these works composed and presented there remain as milestones of modern dance, such as Deaths and Entrances and Letter to the World by Martha Graham, With My Red Fires and Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor by Doris Humphrey, and Trend by Hanya Holm.

World War II began a period of disruption in the careers of the pioneers. The Bennington School of the Dance closed; male dancers were drafted into the armed forces; tours of the "gymnasium circuit" of colleges and universities, long a finan¬cial mainstay of modern dance companies, declined. Financial difficulties forced the disbandment of the Hanya Holm Company in 1944. Miss Holm turned to choreography for Broadway musicals while continuing to teach at her New York studio and at the Colorado College summer sessions.

Nineteen forty-four also saw the end of Doris Humphrey's performing career, owing to an arthritic hip. For a brief time she considered total retirement. But then she found a vehicle for her creativity in Jose Limon, a former member of her com¬pany who had just been released from the U.S. Army. She became artistic director for his company and composed some of her best-known works for it. She also continued to teach choreography.

Following the breakup of his partnership with Doris Humphrey in 1945, Charles Weidman continued to teach, choreograph, and maintain a company and studio theater. Because he had depended heavily on her, he found it difficult going alone as his financial problems grew. However, in spite of the drawbacks, he was able to choreograph a number of important works in the years that followed.

Of the original four pioneers, only Martha Graham was still in full command of her performing powers at the end of World War II. And the peak of her creative career was still ahead of her.

Two other important dancers of this generation were Helen Tamiris and Lester Horton.

Helen Tamiris combined ballet and Delsartean theory learned from Irene Lewisohn to create her own style of modern dance. In 1930 she attempted to unify modern dancers through the cooperative performances of the Dance Repertory Theater, but unification was not to be realized. Together with her husband, Daniel Nagrin, she founded the Tamiris-Nagrin Company in 1960, which was dissolved with her death in 1966.

Influenced by Denishawn, Mary Wigman, the Japanese dancer Michio Ito, American Indians, and ballet, Lester Horton organized a dance company in Los Angeles in 1932, which was notable as the first company to include African-Americans. Although he was aware of the activities of the modern dancers in New York, he preferred to work in isolation from them. Following his untimely death in 1953, some of the dancers from his company continued their own careers, including Alvin Ailey, Carmen de Lavallade, Bella Lewitzky, Joyce Trisler, and James Truitte. Through these dancers Horton's eclectic, indi¬vidualistic technique and choreography were kept alive.

From The Vision of Modern Dance: In the Words of Its Creators, Edited by Jean Morrison Brown, Naomi Mindlin and Charles H. Woodford.

Thursday, November 8, 2007

Ballets Russes

Ballets Russes

The world of ballet was by no means insulated from this revolution of dance-makers. But in a world where dance is made within institutions-a company with a school attached-an innovative dance-maker has no choice but to come to terms with the tradi¬tion that the institution represents. The choreographers who figured prominently in the evolution of ballet in eighteenth ¬and nineteenth-century Europe-men like Jean Georges Noverre, Charles Louis Didelot, Auguste Bournonville, and Marius Petipa-were ballet masters of major companies. They did not have to reinvent dance from the ground up; their innovations rejected some prece¬dents from earlier times while building on others. This was the model envi¬sioned by Mikhail Fokine when, at the time of Isadora Duncan's visit to Russia, he sent an artistic manifesto to the director of the Imperial Theaters. Fokine believed that the great classical tradi¬tion that the Russians had inherited from the French and lovingly nurtured for much of the century-since 1869 under the leadership of Marius Petipa at St. Peterburg's Maryinsky Theater-had gone stale. Fokine revered Petipa but he wanted to let in fresh air. His approach to reform was both aesthetic and scien¬tific. In place of a loosely organized succession of "numbers," "entries," and so on, he called for a unified work of art whose performance would be unin¬terrupted even by pauses for leading dancers to acknowledge applause; in place of "mere gymnastics" and conven¬tional gestures, he called for expressive dancing that would make use of the whole body down to "the last muscle." And, through careful research into the time and place in which each ballet was set, he believed that all elements of a production-"music, painting, and the plastic arts"-could be harmoniously blended to express a single, underlying theme.

The director of the Maryinsky Theater ignored this manifesto but per¬mitted the precociously talented Fokine to dabble in choreography. Fokine had made his debut as a dancer in 1898 on his eighteenth birthday; at the age of twenty-two he was already teaching classical technique to the junior girls at the Imperial Ballet School. In the years following Duncan's visit, he pressed his campaign to reform the Russian ballet tradition. His first efforts to stage ballets with Greek themes and Duncanesque freedom of movement and costume ¬including bare feet and bare knees for the ballerinas - provoked opposition and he was forced to compromise: in one ballet the dancers appeared in tights with toes and knees painted on. The radical nature of his ideas can be appreciated from the comments of a ballet who, a few years later, danced barefoot, for the first time in a Fokine ballet: "This gave me a strange sensation of nakedness, like walking in public in a nightgown."

But gradually barriers fell. In 1906 a production he put together for students won praise from the recent retired Marius Petipa, whose own historical spectacles Fokine had criticized as "unauthentic." In 1908 he present two precedent-shattering works. In Une Nuit d'Egypte, an erotic divertissement featuring Anna Pavlova and himself in the major roles, dancers turned their profiles to the audience in the style of Egyptian tomb paintings, which shocked traditionalists accustomed to the predominantly frontal display of the classical canon; as the hero, Fokine danced with bare knees showing belt the border of his striped kilt; and the ballerinas bent and twisted their upper bodies in unconventional and provocative poses. For Chopiniana he adopter not only the serious music favored by Isadora Duncan but, according to some accounts, her fluid and expressive are movements as well. Another possible influence on Fokine's plastic use of the arms was the appearance in St. Petersburg of a troupe of Siamese court dancers in 1900. In 1905, he choreo¬graphed a brief solo for Anna Pavlova, called The Swan, in which her tremu¬lous arm movements represented the last futile efforts of a dying creature to regain the freedom of flight it had once known; when Pavlova began touring the world with her own company after 1910, this became her signature piece.

For all the excitement provoked by Fokine's innovations, it is by no means certain that he could have realized the full range of his ambitious reforms with¬in the tradition-bound Imperial Ballet. Serge Diaghilev gave him the opportu¬nity he had dreamed of. As tsarist Russia slipped further into financial and political chaos, Diaghilev received per¬mission to bring a troupe of Maryinsky principals to Paris in 1909, with Fokine as ballet master. Audiences in the West were astonished by the technical facility and expressive power of the Russian dancers, who included Pavlova and the nineteen-year-old Vaslav Nijinsky. The settings and costumes by Leon Bakst and Alexandre Benois blazed with color. And the ballets themselves, choreographed by Fokine, challenged preconceived ideas of classical dance.

Yet another of those photographs (left) that have become indissolubly linked with a dancer: Anna Pavlova as The Swan, a solo dance that Mikhail Fokine choreo¬graphed for her in 1905 to music by Camille Saint-Satins. Pavlova's tireless touring with her own company did much to stimulate worldwide enthusiasm for ballet. Like many modern dance-makers she had an interest in non-Western dance traditions. In London she met a young Indian art student named Uday Shankar; he helped her stage, and danced with her in, Radha-Krishna (1923) and other dances below). Shankar (1900-77) became a forceful popularizer of Indian dance in the West; in his later years he worked to reinvigorate traditional dance forms in India.

In Cleopatre, an adaptation of Une Nuit d'Egypte, the queen and her paramour made love on stage (discreetly hidden behind veils) while half-naked slaves and attendants cavorted orgiastically. Scheherazade featured an even wilder orgy and a merciless massacre onstage.

For three years, triumph followed triumph, confirming Fokine's dictum that choreographic style should change from ballet to ballet in accord with theme and music. The same audiences that thrilled to Fokine's acrobatic "Tar¬tar" dances set to music from Borodin's

opera Prince Igor were deeply moved by the abstract Romanticism of Les Sylphides, a revised version of Chopiniana, which emerged as the first entirely plotless ballet. In 1911 Fokine collaborated with Igor Stravinsky on Petrouchka, a Russian folk tale, with Nijinsky in the title role; this charac¬ter's jerky, mechanical movements and turned-in toes dramatized his helpless¬ness as a puppet of fate.

Fokine broke with Diaghilev in 1912, and although he later returned to the Ballets Russes, he never again equaled his innovative achievements during those first three Paris seasons. Diaghilev, whose financially shaky company need¬ed a steady supply of novelties to attract audiences, was neither a choreographer nor a dancer nor a composer nor an artist of any kind. Yet he had a hand in every aspect of the works his company produced. It was his idea to present three short ballets in a single evening, a format which has become standard for ballet companies around the world. He hired, and fired, and rehired the Stravinskys and Saties, the Fokines and Nijinskys, the Baksts and Benoises, the Picassos and Cocteaus whose talents merged in such exciting and often sur¬prising ways that the contributors fought bitterly for years over who deserved credit for which aspect of this or that ballet. All his ballet masters--Fokine, Nijinsky, Leonide Massine, Bronislawa Nijinska (Nijinsky's sister), and George Balanchine - were extraordinarily talented, and he rarely second-guessed them; but their average age when he took them on was under twenty-three. There was never any doubt about who was in charge. Ultimately, it was Diaghilev's taste that was reflected in the style and the content of the Ballets Russes; his unique company was his instrument of self-expression.

When Vaslav Nijinsky, the most acclaimed male dancer of his day, began creating innovative ballets for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in 1912, it looked for a time as if the young Nijinsky might achieve the choreo¬graphic goal that had eluded Fokine: to mold a first-class ballet company into a means of personal expression.

Nijinsky was born in Kiev in 1890 of Polish extraction. His parents headed their own touring dance company in Russia; from an early age he and his younger sister Bronislawa appeared on¬stage with their father, who was noted for his enormous leaps. At the age of ten, Nijinsky enrolled in the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg, where his teachers recognized his natural tal¬ent almost immediately. On graduation in 1907 he danced a succession of im¬portant roles in such ballets as Giselle, Swan Lake, and The Sleeping Beauty.

His dancing offered a rare mix of strength and facility. Propelled by pow¬erfully muscled thighs, his leaps were legendary not only for their height but for the impression he gave of pausing in midair at the top of the arc. In the words of critic Edwin Denby: "When he moves he does not blur the center of weight in his body; one feels it as clearly as if he were still standing at rest, one can fol¬low its course clearly as it floats about the stage through the dance." He pro¬jected a vitality, a sensuality, that some saw as innocent, others as erotic.

Among his admirers was Serge Diaghilev, who sensed that a great ballet company could be built around this young dancer who combined a rig¬orous schooling in classical technique with an almost palpable emotional intensity.

The roles that Fokine choreographed for Nijinsky in the first three seasons

of the Ballets Russes allowed the dancer to display the full range of his powers to wildly appreciative audiences in Paris and London. As the Poet in Les Sylphides he embodied an abstract Romanticism seen through the lens of nostalgia; as the Favorite Slave in Scheherazade he was the devotee of sexu¬ality for whom even death is a kind of orgasm; in Le Spectre de la Rose his leap¬ing exit from the stage had the sensa¬tional finality of a record-setting broad jump; in Petrouchka he was poignancy itself. There was, it seemed, nothing he could not do, no role he could not bring to life onstage. He always had trouble communicating in words, but when he danced, he spoke with his entire body. Is it any wonder that, prompted by Diaghilev, he decided to take the next step and try his hand at making dances?

Having mastered technique as few dancers before or since, Nijinsky apparently had no interest in devising ever-more-challenging exercises in the traditional mode. Instead, he took up where Fokine had left off-seeking to express something of himself through the artistic medium of a classically trained ballet company.